‘Don't be ashamed of wanting to excel as an educator’

Now excellent educators too can achieve the rank of associate professor or even professor thanks to Recognition and Rewards.

Seated at a table in Neuron, three assistant professors from three different departments are in conversation. They have one thing in common: an intense passion for education and the ambition to build a successful career as an educator at our university. Thanks to the education profile in Recognition and Rewards this is finally possible.

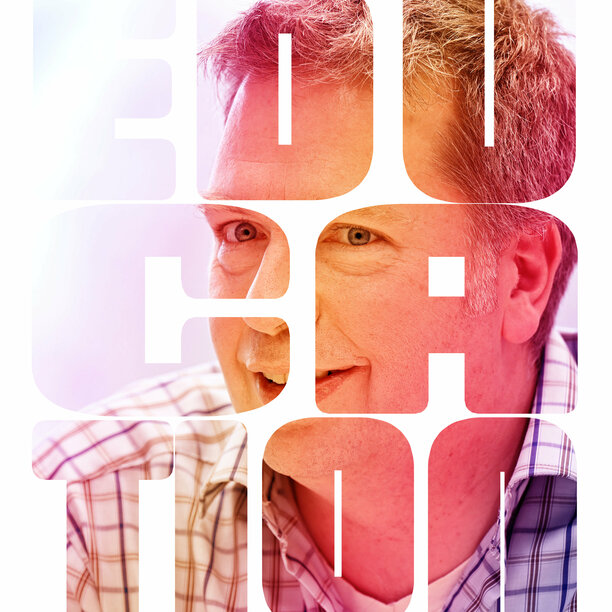

Thorough groundwork preceded the writing of this article. This could be seen as illustrative of the path on which assistant professors Wouter Ellenbroek, Rob Mestrom and Peter Ruijten-Dodoiu find themselves. In their academic careers they have reached the crossroads between research and education. Thanks to Recognition and Rewards they can follow their educator’s hearts and, by choosing the education profile, can build a career at the university. As this profile is still in the pilot phase, they are among the first to take this route.

After a preliminary chat they are keen to work on an article about their choice to pursue education. Either with no hesitation, or with some trepidation. “Speaking openly for the first time about what you want...that's quite something, isn't it?” explains Rob Mestrom, assistant professor in the Electromagnetics group at the Department of Electrical Engineering. “And it means leaving the well-trodden path at the university.”

A prof said, ‘You don't want to churn out lessons for a living, do you?’ But that's precisely where I can make an impact.

Assistant professor Rob Mestrom

“Why is that?” asks Peter Ruijten-Dodoiu, assistant professor in the Human-Technology Interaction group at Industrial Engineering & Innovation Sciences. Mestrom replies: “There's a traditional career path at the university and everyone follows it: you do research, supervise PhD candidates, write papers, apply for grants and then you're promoted from assistant to associate professor, and finally to full professor. People in education are often viewed as oddities. A professor once said to me ‘You don't want to churn out lessons for a living, do you?!’ But that's precisely where I can make an impact.”

Stigma

“The biggest barrier is still that stigma, the feeling that by making this choice you're conceding defeat,” confirms Wouter Ellenbroek, assistant professor in the Soft Matter and Biological Physics group at the Department of Applied Physics & Science Education. “Don't be ashamed of wanting to excel as an educator.”

Ellenbroek had no doubts at all about going on the record about his passion for education. “I'm long past believing that choosing an education profile means you're batting in the B league. Even so, I know that when you decide not to apply for a Vici grant or an ERC Consolidator grant, there's a haunting sense of throwing in the towel.”

I'm long past believing that choosing an education profile means you're batting in the B league

Assistant professor Wouter Ellenbroek

“To get on in your career as a scientist, you have to apply for one personal grant after the next. I found that system off-putting. It revolves around the achievements of a single individual and that's not how I do science. I prefer to work in teams and that's how I'm building my profile. Luckily, I have a dean who fully supports my ambitions,” says Ellenbroek.

The right mix

Mestrom likewise feels supported by his dean and the chair of his group. “I've been umming and ahing about my career focus for the past three years,” he says. “But it only started gnawing at me when Recognition and Rewards was introduced two years ago. That's when I decided to go for the education profile.”

Mestrom: “My ambition to focus on teaching is also supported within my group. We complement each other. My manager is working on valorization and applying for grants, I assist him, but focus on innovations in education. It's something you have to keep on talking about within your group.”

“That's what gives the group its mix; they need you as much as you need them,” concludes Ruijten-Dodoiu. “You have to look at the tasks from the group level. Who's doing the research, who's doing the innovation in education, who's ensuring impact - the narrative the group puts out in the wider world. In any group, in order to be successful, you need all sorts of people.”

In any group, in order to be successful, you need all sorts of people.

Assistant professor Peter Ruijten-Dodoiu

The road to promotion

Moving up within the education profile from, say, assistant to associate professor requires a fair amount of preparatory work. The candidate must submit a research statement, a teaching statement and a narrative curriculum vitae before they can ‘go before a BAC’. Here, you have to defend your promotion before a Promotion Assessment Committee (BAC). “In these documents you have to look back and look head, but the level of detail required in these statements is still not entirely clear to me,” says Ellenbroek.

He spoke with the HR advisor about how he needed to approach this. “But they were new to this, too. I'm the first person in our department to do this, so I'm a bit of a guinea pig.”

After the summer Mestrom wants to work towards his BAC, “then hopefully I'll become an associate professor sometime within the next two years. This is pioneering work; we don't yet know the ropes, but we all want it to succeed,” says Mestrom. “Its success also depends on putting the right people up before the BAC.”

All being well, the doctorate of Ruijten-Dodoiu's first PhD candidate will be signed, sealed and delivered sometime after this coming summer. That will give him the long-awaited check he needs to become eligible for UD1. “At every step on the ladder you're met with a checklist of requirements. Neither passion nor intrinsic motivation will fill it in. I'm busy preparing the documents they're asking of us and dovetailing them to my education profile. Then I hope to be able to go up before the BAC in the fall.”

That's how it works in science: first you do the job, then you're given it.

Assistant professor Peter Ruijten-Dodoiu

“I feel like I've spent the last couple of years functioning at the level I'm now applying for,” says Ellenbroek. “That's how it works in science,” confirms Ruijten-Dodoiu. “First you do the job, then you're given it.” “I'm in no hurry,” says Ellenbroek, “although I get a lot of verbal appreciation and it would be nice for once to see it in writing.”

Publishing about education

“The education profile is much broader than just teaching,” says Ruijten-Dodoiu. “I'm also researching innovation in education and building an international network in the field. I go to education conferences and I publish articles on Challenge-based Learning and other innovations in education, like those that were introduced at innovation Space. Is that something you both do, too?” he asks the others.

“It's certainly a wish of mine,” says Mestrom. “I want to know, for example, how a new method impacts students and their success rate. You have to run a course a number of times before you know anything for sure.”

Subfields and niches

Ellenbroek: “You can only become a full professor once you've gained an international reputation for your innovations in education. So remarkably few people are going to make the grade. It is much easier to make a name for yourself in research, with its many subfields and niches. If you work in a very specific area, everyone in that field knows who you are; you keep running into each other. Education is a much broader field, so it's more difficult.”

Ruijten-Dodoiu doesn't believe that things are all that different for them as education innovators. “If you're looking for specific, you can go to conferences in our own field, engineering education. I've already been asked a couple of times to give a presentation at an education conference.”

Ellenbroek: “I spend 70 percent of my time on education and 30 percent on research, even so more people know me for my research.” “Then it's time to publish something,” says Ruijten-Dodoiu. “I started moving in that direction here on the campus, talking about ISBEP and Challenge-based Learning. This summer, for example, a CBL conference is being held at TU/e. I'll be speaking, together with a colleague, and that will no doubt lead to more invitations to talk about our methods. It's one step at a time.”

The future

When asked ‘Where will you be in five years' time?’ Mestrom answers dryly. “I think by then you'll be sitting here with two UHDs and a UD1.” Then, seriously: “I hope that by then I'll be enjoying my work as an educator as much as I do now, and enjoying due recognition. There's no shortage of ideas for innovations, you know. A bachelor's course that integrates math with applications within Electrical Engineering; a master's course - medical device design - in which engineers learn to work in compliance with the latest medical regulations. Five years from now I'll have validated and rolled out these ideas, and I'll be working at departmental level on vision and policy.”

Mestrom: “I'm not necessarily looking to becoming a full professor asap. I'm very satisfied with what I'm currently doing and I don't want to give up the teaching and contact with the students. It's here that I feel I can make a real impact.”

“Whether I'll be a professor in five years' time, that's something for the long term. First of all, I need to make UHD2, hopefully this year,” says Ellenbroek. “If things move fast, I wouldn't rule out aiming for UHD1. But I'm not in any hurry, although it would be nice not to stop hearing ‘You've been here ten years and you're still an assistant prof?’”

Program director

Ellenbroek very much enjoys the organizational side of education and sees himself as eventually becoming program director for his department. “Over the past five years I've taken on more and more tasks in education and it's work I thoroughly enjoy. I feel valued. If the position ever falls vacant, I'd be an obvious person for them to consider.”

“I hope that in five years' time I’ll have gained a national and international reputation as an expert in the field of testing in Challenge-based Learning and that we have been able to persuade other lecturers of the importance of CBL and other innovations in education,” says Ruijten-Dodoiu. The dream position in this scenario is that of program director. “But more than anything I hope that I'll still be doing things I enjoy. Let's wait and see what position goes hand in hand with that.”

It's inconceivable that someone so driven to innovate in education would get stuck as a UD.

Assistant professor Wouter Ellenbroek

“It would be crazy if you didn't become a UHD,” says Ellenbroek to Ruijten-Dodoiu. “If this university takes Recognition and Rewards seriously, it would be inconceivable that someone as driven to innovate in education as you are would get stuck as a UD. That would be strange. And there's a message here: This career path doesn't come in just one shape and size. You have to be able to develop and grow in the direction you enjoy and in the work you're good at. Do that and the university has the most to gain, too.”

Our stories on Recognition and Rewards

More on our strategy

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/c/f/csm_BvOF_2024_0319_AEV_license_TUe_Dirk_van_Meer_-_CORE_1__c976e259a5.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Rob Mestrom. Foto: Bart van Overbeeke Bewerking: Pantelis Katsis](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/9/9/csm_RWRob_06c02717a9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Peter Ruijten-Dodoiu. Foto: Bart van Overbeeke Bewerking: Pantelis Katsis](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/3/3/csm_RWPeter_2f613718d7.jpg)