Traveling salesman with two suitcases of scrap metal

Alumnus Piet van Rens receives Lifetime Achievement Award for his work within the Dutch precision engineering community.

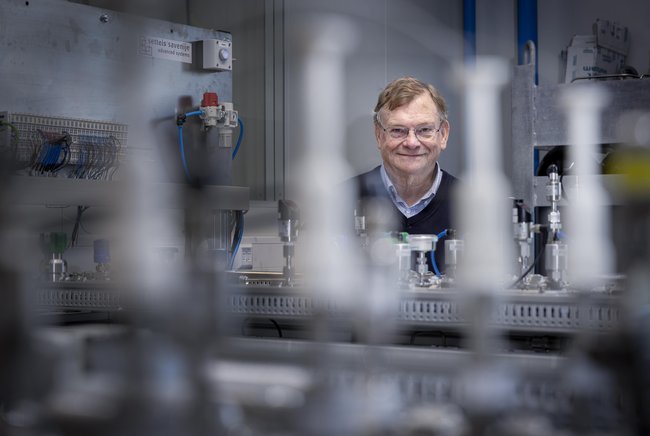

The American Society for Precision Engineering recently awarded its annual Lifetime Achievement Award to TU/e alumnus Piet van Rens. While he is regarded as one of the pillars of precision engineering in the Netherlands, he himself feels he is being unduly celebrated. “Evidently, a traveling salesman with two suitcases of scrap metal and a passion for imparting knowledge can come a long way.”

Beneath the brim of a large leather hat, his features at first glance appear impassive, but in fact Piet van Rens is often deep in thought as he strides across the TU/e campus. Since retiring a few years ago, he can usually be found in the Meulensteen House of Robotics. Here, the team at TU/e spin-off Eindhoven Medical Robotics are benefiting from his high-precision advice.

“It didn't help that my retirement coincided with the start of the corona pandemic, but I soon realized that I'm not cut out for sitting at home.” And so when TU/e professor Maarten Steinbuch asked him to apply his brains to the field of high precision robotics, the timing was perfect. Now he enjoys traveling up to Eindhoven every week, always with a full briefcase by his side. “We discuss the day-to-day problems and I try to uphold the fundamentals of mechanical engineering in precision engineering. In all these years, the way of thinking hasn't changed.”

The Devil's Printbook

His own way of thinking was formed in the early 1970s by his famous teacher Wim van der Hoek, endowed professor at THE, Eindhoven's technical college and the forerunner of TU/e. Van Rens learned about compressive forces using a cheese grinder and often sat down with Van der Hoek and other students to sketch out ideas, be they brainwaves or clangers, on a huge sheet of paper. This work provided the basis for the renowned The Devil's Printbook, which became a manual used by the Dutch school of construction. A global success, whose influence still filters into today's high-tech mechatronics.

And so this coursebook full of construction principles, to which he contributed, is something Van Rens often brings along in his briefcase. “In a workshop we'd work on somebody else's failed working out of a problem, and step by step the experience taught you logical reasoning. And while your own mistakes might be the most instructive, it's certainly cheaper when it's someone else making the error. At the same time, it was very good for developing a bit of self-confidence. If you put forward a good point, Van der Hoek could easily inflate its importance. And you'd sit there proud as punch because you'd had a great idea - an experience not to be undervalued for the more introverted amongst us.”

Mechanical engineering in day-to-day life came as a revelation to Van Rens. It formed the basis of his own way of teaching, which he adopted early on. Having graduated, he was lecturing part time at TU Delft. With a practical purpose in mind, he explains with some reluctance. “During my graduation year, I had to give a presentation to the Netherlands Association for Measurement Technicians. It cost me all my evenings for a whole month and the result was a lecture that was shockingly below par. A graduate who couldn't give a lecture, that, to my mind, was simply unacceptable. Having to prepare a lesson once a week for a group of students proved the perfect training ground.”

Bike builders

At Philips Beeldbuizen (the cathode-ray tube division) he set up a course called ‘Mechanical Engineering for Laypeople’ and his love of imparting knowledge, usually in an unconventional manner, grew. “Our profession (mechanical engineering or werktuigbouw) isn't only a science, you can also see it as a craft,” Van Rens chuckles. “We build (bouw) gear (tuig) that works (werk) - a craft that requires both math and common sense. We were sometimes jokingly called ‘bike builders’. I didn't mind.”

His course ‘Construction Principles’ at the Philips Centre for Technical Training was meanwhile gaining a reputation in the region. Van Rens later added training sessions for Mikrocentrum to his portfolio. As a result, entire cohorts of engineers in various high-tech companies were taught the fundamental principles of precision engineering with the help of frame tubes and bicycle spokes, after which they never looked at a bike in the same way again.

NASA watched our design like hawks

A cooperative alliance with space agency NASA enabled Van Rens to take this informal manner of schooling overseas. The success that followed took the Americans by surprise. “It was their first encounter with the principle of statically determinate structures. They watched our design like hawks, six strange skinny legs and a special suspension that Wim van der Hoek had pushed for. When our component was the only one to survive the satellite mission unscathed, the phrase 'magical instrument' was on everyone's lips. The prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) adopted our new way of thinking, and more and more US companies wanted to know about this form of light, stiff design with an absence of play.”

The courses Van Rens has delivered over many years are highly regarded within the American Society for Precision Engineering, where he has been praised for his practice-oriented approach. A traveling salesman with two suitcases of scrap metal, says Van Rens with a smile - his bike parts and demo models accompanied him wherever he went.

Whereas Wim van der Hoek is regarded as the founder of the construction principles of precision engineering, the American Society for Precision Engineering describes Van Rens as one of their greatest propagators. His contributions can be found in many of the ultra-high precision machines in use today. He is still teaching new students at Eindhoven Medical Robotics the finer points of precision engineering, and advocates paying more attention to the role of step-by-step logical reasoning.

“In engineering, convincing your colleagues with arguments is the way to prove you're right. This makes the ability to explain why you've done something very important. The value of this is sometimes underestimated by our current students.” It is one of the reasons why he used to emphasize the importance of soft skills courses at high-tech companies such as ASML, and why he still has some indirect involvement in this area.

Alma mater

After a successful career he is back at his alma mater, more by accident than design, he says; Eindhoven Medical Robotics rather than TU/e brings him here. “I sometimes speak to former colleagues, of course, but it's usually within the context of one or other cooperative alliance with Philips; there are many of them. To be honest, in some way or another I worked on every product that Philips produced back then,” he admits with a shrug. “I was given a very thorough training at THE and took that into industry. It's nice to think that I, in my turn, can pass on to today's students this knowledge mix and the importance of practical training.”

More on our strategy

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/c/f/csm_BvOF_2024_0319_AEV_license_TUe_Dirk_van_Meer_-_CORE_1__c976e259a5.jpg)