Jan van Hest is constantly striving for innovation

Jan van Hest combines biology and chemistry in such a way that the boundaries between the two disciplines become really blurred.

2020 has been a difficult year for many people, including our researchers and students. Fortunately there were some bright spots. In the summer, one of our brightest minds, polymer chemist Jan van Hest, was awarded the Spinoza Prize, the most important award in Dutch science. Unfortunately, due to corona, the official presentation of the prize in September could not take place. We therefore like to put Jan van Hest in the spotlight again by publishing this portrait, in both text and video, which appeared earlier on the website of the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Focusing solely on interesting issues rather than disciplines and constantly developing yourself. That’s essentially the formula for success that Jan van Hest, professor of Bio-Organic Chemistry, used to create a completely new field of research on the interface of biology and chemistry.

Looking back, it’s not surprising that he has integrated biology and chemistry into his work, says Jan van Hest, sitting in his office at Eindhoven University of Technology. "These were already my favourite subjects in secondary school. I eventually decided to study chemistry, because it seemed easier to move towards biology from there than the other way around."

The student from Tilburg graduated in polymer chemistry at Eindhoven University of Technology in 1991. "Around that time, Bert Meijer set up a new organic chemistry group there that focused on dendrimers – highly branched polymers. The idea of being part of such a new group appealed to me."

Jan uses the same kind of creative thinking as an artist

Meijer, himself a winner of the Spinoza prize in 2001, has no trouble recalling those early years. "Jan was the first PhD student that I was able to appoint myself. His doctorate was a huge success. We developed the first amphiphilic block copolymer – a gigantic molecule consisting of blocks of different polymers that assembles in water. That was complicated precision work. You start with a polymer onto which you keep attaching new pieces of a dendrimer. That means repeating the same reaction on the same polymer 32 times, always analysing precisely what you’ve created and how that molecule behaved. The article in Science in which we described this process was one of the highlights of my early career".

Moving towards biology

With a doctorate in his pocket, Van Hest left for the United States to become a postdoc in David Tirrell’s group at the University of Massachusetts, where he learned the ropes of protein engineering. This was a new field that used polymer chemistry to modify existing proteins or to design new ones. "At the time, we could only use a small set of building blocks from nature. Jan’s background in organic chemistry meant he could help us decide which molecules could be suitable for expanding this set of useful amino acids", says Tirrell. Although the young Dutch postdoc only worked in his group for a year, he left an indelible impression on his American supervisor. "Jan is a creative and lively person, who even then knew how to inspire my whole group. He combines biology and chemistry in such a way that the boundaries between the two disciplines become really blurred. He uses chemical structures when he can but switches to biological building blocks just as easily if it serves his purpose better."

Personal development

"I had received an award for my PhD thesis from DSM, who immediately asked me to come and work for them. I had set my sights on the postdoc position first, however, because I thought it would be good for my personal development. When I returned to the Netherlands, I accepted their offer, because I wanted to know what it’s like working in industry. A great deal of what I learned in those three years about cooperation and organisation is still useful today for managing my research group and institute."

Van Hest continued to be drawn to science, however. "I want to discover new things and educate young people. There’s less opportunity to do that in a company." Just when he was thinking about his future, he received a message from Radboud University in Nijmegen. "Their professor of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Binne Zwanenburg, was about to retire. They asked me to apply, even though that wasn’t my specialisation at all." The young chemist went to Nijmegen, without too many expectations. "That was the most relaxed job interview ever. I mainly saw the interview as a great opportunity to outline my vision of the future of Bio-Organic Chemistry."

Jan combines biology and chemistry in such a way that the boundaries between the two disciplines become really blurred

Roeland Nolte, emeritus professor of Organic Chemistry at Radboud University and then director of the Nijmegen Institute for Molecules and Materials, also remembers the application procedure well. "We had an excellent candidate to succeed Zwanenburg, Floris Rutjes. However, the list of applicants also included Jan van Hest. I already knew him, because I had been his second PhD supervisor. At the time, I wanted to push research in Nijmegen into a different direction by attracting young people with new ideas. The fact that Jan had experience working in industry was a plus. I immediately began making arrangements for the appointment of two professors, instead of one. That worked out very well."

Seeking collaboration

It wasn’t easy to be appointed professor at the age of 31, Van Hest says in hindsight. "Those were really testing times, but I would have been crazy to miss out on such an opportunity. I swapped a permanent job for a temporary one and was expected to prove myself and develop a field of study within five years. You’re bound to run into funding problems if you don’t have a track record yet, though, especially if you’re trying to launch a new field of study in the process." Van Hest solved these problems by working together with his Nijmegen colleagues Roeland Nolte, Alan Rowan and Floris Rutjes. "By collaborating, we were able to build critical mass, which enabled us to achieve excellent results within three years."

My environment has a decisive influence on the direction my research takes

One of the subjects that Van Hest and Rutjes collaborated on was research into microreactors. "That was a completely new direction for Nijmegen at the time’, says PhD student Pieter Nieuwland. "My fellow PhD student Kaspar Koch and I investigated the possibility of using lab-on-a-chip applications in organic and bio-organic chemistry." Eventually, this partnership led to the establishment of the company FutureChemistry, where Koch is managing director and Nieuwland director of technology. "Jan is still involved in our company as a scientific adviser, although what we do now is no longer closely connected to his research. We still make grateful use of his enthusiasm, his knowledge and his extensive network to this day."

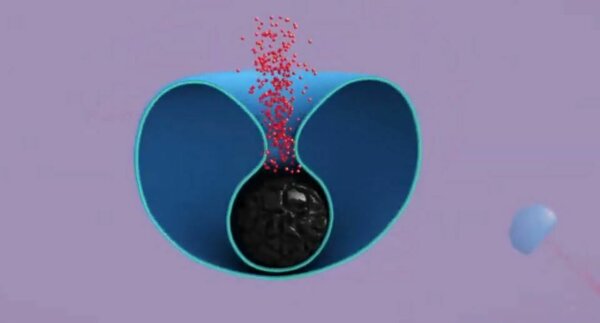

Meanwhile, Van Hest had shifted his research to making artificial cells and cell organelles – structures that can fulfil a certain function in a cell. Among other things, he made nanoreactors and hollow spheres produced from polymers, which you can fill with medicines or with biological components such as proteins. "We’re using these to develop systems to tackle diseases, for example by locally releasing enzymes that can inhibit or cure metabolic diseases", Van Hest explains.

Intuitive, original and creative

What typifies Jan van Hest as a scientist? According to his mentors, he always explores the possibilities, after which he carefully chooses what to focus on. "He has shown that his intuition is well developed and that he knows how to choose the right subjects", David Tirrell says. "Jan uses the same kind of creative thinking as an artist", says Roeland Nolte. "Jan has combined the knowledge and skills he acquired during his postdoc period in a completely original way with his PhD work, and in doing so he has created a completely new field of study of which I have high expectations", Bert Meijer explains. Meijer is pleased that Jan has succeeded him as scientific director of the Institute for Complex Molecular Systems. "And, of course, as his PhD supervisor, I’m proud that he has now received the Spinoza Prize."

I often feel like an explorer or professional athlete competing with the whole world

After seventeen fruitful years in Nijmegen, in which he not only published many breakthrough articles on a wide variety of subjects but also launched four start-ups and registered several patents, Van Hest thought it was time for a new challenge. In 2016, he returned to his alma mater in Eindhoven. "My environment has a decisive influence on the direction my research takes. A change of environment gives me a fresh stimulus and creates new contacts, and that ultimately leads to new insights."

He’s currently working on artificial endosymbiosis – the implementation of artificial organelles in a living cell, or vice versa. "Only two groups in the world are working on this. We can really make significant progress in this area at Eindhoven." That’s an important consideration for his selection of subjects, says the chemist. "What’s going to be important? And how can I contribute to that? For example, I worked on spider silk for a while. When that subject reached a certain maturity, the added value I could offer with my group was limited. That was a good time to switch to something else."

Explorer as educator

After all those years in science, Van Hest still loves doing research. "I often feel like an explorer or professional athlete competing with the whole world. And I’m allowed to teach young enthusiastic people how to function in society. Ultimately, all the knowledge you gain automatically becomes obsolete and forgotten. It’s these people who are my real legacy."

Van Hest advises his students to follow their dreams and not shy away from engaging in a new subject with a certain degree of naivety. "Start with something new because you think it will become important, and then learn as you go along. I try to instil sufficient confidence in my students to give them the courage to do that, just like my mentors instilled it in me."

Source: NWO

Find out more

More on our strategy

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/c/f/csm_BvOF_2024_0319_AEV_license_TUe_Dirk_van_Meer_-_CORE_1__c976e259a5.jpg)