Back to the Beginning: Radio waves from the deep space past

After four years in Australia, Mike Kriele returned to the Netherlands to defend his thesis and shared his research on the Square Kilometer Array.

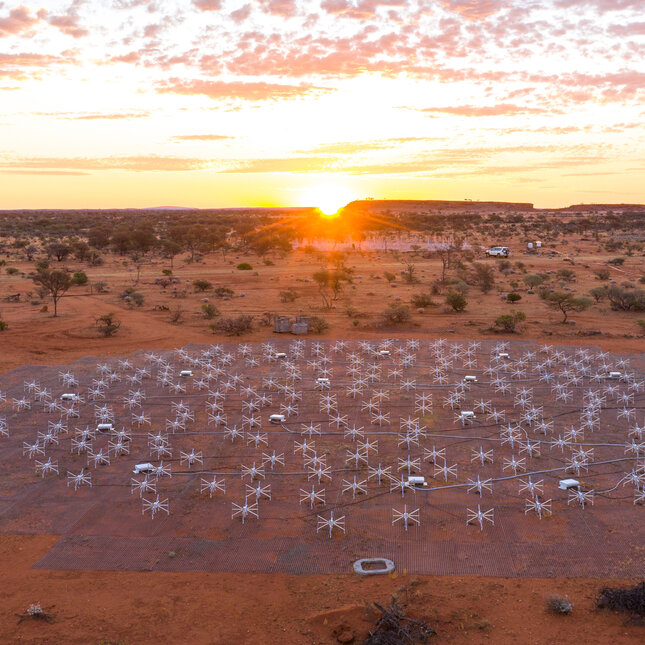

In order to pick up radio signals from the very first stars – some 13.5 billion years ago – you need an overview of all the signals emitted by more recent galaxies. Radio astronomer Mike Kriele set out to Australia to work on a test setup of the ambitious Square Kilometer Array, the world’s largest radio telescope that is expected to shed more light on the earliest stages of the universe.

In the middle of nowhere, some 800 kilometers from Perth – the Western Australian university city that has been home to TU/e PhD student Mike Kriele for the past four years – is a vast telescope park.

The night sky looks magnificent there, says Kriele with a twinkle in his eye. “Forget all the other starry skies you’ve ever been under. I saw orange and purple, I saw the Milky Way like I’d never seen it before, and so many shooting stars. It’s absolutely incredible. Space looks so vast from there that you become very aware of how insignificant you are. An extraordinary experience.”

It was on the advice of Electrical Engineering program director Mark Bentum that the then UT student first arrived in Perth for a master’s internship. He also wanted to go there to visit his distant relatives. Australia suited him very well – “a laid-back culture, friendly folks, a lovely climate, and the opportunity to swim in the sea all year round” – and, as often happens, Kriele was offered a PhD position.

In consultation with Mark Bentum, who had been appointed professor of Radio Science at TU/e in the meantime, a collaborative project was launched. The idea was to roughly divide his research time between the two universities, but the Covid-19 pandemic threw a spanner in the works. For the first time since August 2018, Kriele returned to the Netherlands, and defended his dissertation at the Department of Electrical Engineering on December 13th.

Childhood dream

A great adventure, that is what it sounds like when Kriele talks about his doctoral studies. After all, it is quite an honor to indirectly contribute to the development of the Square Kilometer Array, an international research project to build the largest radio telescope in the world.

It is a childhood dream come true, Kriele admits. As a small child, he would spend hours recreating space shuttles and space stations with Lego bricks, with a shelf full of space books in his room. That fascination grew when he learned about wireless communication and radar during his studies. “It never ceases to amaze me. Technically, you just stick a metal pole in the ground that picks up signals and converts them into currents, but the result is a picture of what the universe looks like.”

Still, Kriele is not so much interested in what he can measure directly, but more so in the things that cannot be measured.

“That does indeed sound very paradoxical. However, if we look at the formation of the universe, we see a lot of activity and heat at the beginning, followed by a long period of time where that suddenly stopped. Eventually, the universe came back to life, seemingly out of nowhere. We would like to see the very first stars. Because if we know more about those, we can probably learn more about that ‘dead’ period. What happened there? The signals from the first stars were emitted about 13.5 billion years ago. However, the longer a signal travels, the more energy it loses. Moreover, the universe is expanding, and as a result, those signals are being stretched as well. Add to that the fact that, for example, the Milky Way or other galaxies that formed more recently are emitting much more energy and overshadowing the weaker signals. That is why we need a model that shows every signal that is being emitted in the universe. Then it will become clear to us which signals are ‘noise’ that should be ignored in our measurements. Once we manage to do that, the faint signals from those very first stars will be within our reach.”

A complete picture of the universe

In order to obtain that total overview of radio signals from the universe, Kriele worked on a new, more accurate observation method.

“Up to now, we have mainly been cutting and pasting, a method we call “snapshot imaging”. This involves measuring radio waves, looking at a small piece of space and immediately snapping a picture of it. Then you move on to the next piece, and so on, until you have mapped the entire universe in tiny pictures. The biggest problem is that this pasting method is not without its flaws and especially around the edges, errors can occur. Snapshot imaging is a great method if you’re interested in a small, specific part of the universe. But if you want to create an overall picture or look at very large objects, you run into all kinds of technical problems.”

That is why Kriele tried out a different method of observation: diffuse sky mapping through the use of spherical harmonics; also referred to as “m-mode formalism” within the field. To put it very simply, he first scans the radio waves of the entire universe very slowly and afterwards, he can make corrections to account for the earth’s rotation.

Huge plain

The first results are promising – of course, there is still a lot of polishing to be done – but it seems that m-mode formalism does indeed produce a much more precise picture of the universe.

Kriele also implemented this new method on a test system for the Square Kilometer Array, which was recreated in the telescope park. It is not exactly easy to reach, he explains.

“During the time that you’re on site – usually for a week – you stay at a container camp or at a wool farm. You get up at five a.m. every morning and then spend three hours driving a four-wheel drive on dirt roads. You have to stay ahead of the rain, or else you’ll be stuck for a few extra weeks. The telescopes are located on a huge plain. There is running water and electricity on site, but other than that, it’s back to basics. Those starry skies, however... Also, because the location is on indigenous territory, you always have to be introduced to the customs of the First Nations people (the country’s original inhabitants, Ed.) by a representative. I considered it a privilege to be able to learn so much about their culture and traditions.”

After his PhD at TU/e, Kriele will go back Down Under – “but first, I’m going to eat a whole lot of kroketten, I’ve sorely missed them” – to receive his doctoral degree there as well.

There is already a new challenge on the horizon: he intends to use a new system to make dome antennas at the SKA in South Africa move simultaneously. All this with a view to the beginning. “Because that will also help us learn more about the evolution of the universe, and what awaits us in the future. So yeah, it’s quite the honor to be involved.”

Title of PhD thesis: High precision mapping of the diffuse low-frequency sky. Supervisors: Mark Bentum, Randall Wayth (External), and C.M. Trott (External).

Source: Cursor.

Media contact

Latest news