This interview highlights the work of three scientists at the Cyber-Physical Systems Center Eindhoven (CPSe):

Jeroen Voeten (scientific director and full professor), Sofie Haesaert (assistant professor) and Jeroen van Dam

(PhD candidate and program manager).

What about a recent achievement. What’s been your proudest moment in the last 12 months?

Jeroen Voeten: My biggest challenge was to bootstrap the center. Within one year, four different Electrical Engineering groups came together. The Electrical Energy Systems (EES) and Electromechanics and Power Electronics (EPE) groups are especially knowledgeable in the physical aspects of systems, while the Control Systems (CS) and Electronics Systems (ES) groups have a lot of expertise on the cyber side. Together we form a unique symbiosis of two worlds that enables us to address the societal and industrial challenges of E-Mobility, High-Tech Systems and E-Grids. Challenges that none of us can solve on our own. At this moment, 18 scientists are affiliated with the center, in addition to three program managers, a secretarial office and a scientific board. This collaboration is already paying off. Based on a unique roadmapping process in which scientists sharply articulate their research propositions, we have already acquired impressive research funding. We did particularly well in the last ECSEL Joint Technology Undertaking (JTU) call. CPSe managed to get involved in four out of the 14 proposals that were granted across Europe. That’s 2.5 million Euros spent on CPS research!

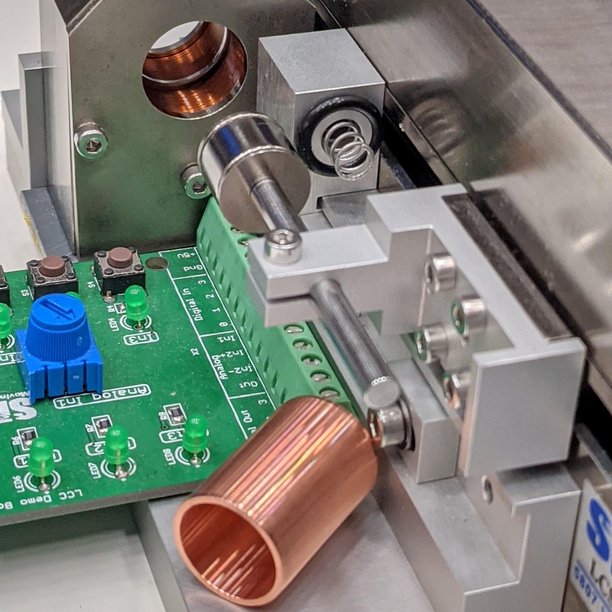

Jeroen van Dam: One of the most important contributions of my thesis has been building a test rig. We spent the past half year working on a test setup for the binary valve actuator. This was a real challenge, especially due to the Covid-19 restrictions. The entire design and mechanical drawings had to be discussed with multiple parties via video conferencing. But our efforts paid off. We were able to run tests in which we used two back-to-back linear motors, one resembling the load and the other the actuator. We are currently applying the experiments to validate my models, after which we will continue with control algorithms proceeding towards soft-landing, a difficult-to-achieve system feature that necessitates the CPS level of abstraction. With this I will wrap up my thesis work. I am looking forward to publishing my results so that I can inspire new researchers to build on it. Further electrification of transport is key to green, autonomous and safe mobility. And a lot more research is still needed to get there.

Sofie Haesaert: A few months ago, I was awarded a VENI grant (a prestigious Dutch grant given to highly promising young scientists) by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). While I’m very proud on a personal level, I’m also extremely excited about the opportunities this grant will bring me. It’s going to give me the chance to strengthen my research on the interface between system identification, control, and formal methods. These areas have evolved rather independently in the past. Truly bringing them together is one of the grand scientific challenges to be addressed by CPS research.

It certainly seems an exciting place to work. Do you have any advice for someone who’s considering a career at TU/e?

Jeroen van Dam: TU/e is a very interesting place to work. Professor Lomonova gave me the opportunity and the trust to take on some really challenging PhD research over the last few years. She also introduced me to CPSe and the possibility of a career switch once I have finalized my PhD. TU/e gives you this kind of freedom. In my role as a project manager, my tasks revolve around supporting scientists to formulate research propositions, attracting research funding, screening candidates for vacant research positions, and the daily management of projects. Someday, I might consider exploring my options in industry, but I am certain that my ties with TU/e will be long-lasting.

Jeroen Voeten: I have been working for the TU/e for my entire career – almost 30 years now. For 15 years I was also employed at ESI (TNO) as a research fellow, developing and supervising applied research and innovation projects in tight collaboration with industry – mainly ASML. This resulted in several industrial innovations, one of which is actually integrated into all of ASML’s latest TWINSCAN machines. I find it exciting to realize that almost every chip that is created in the worldis touched by this innovation. It is this knowledge and experience, about bridging the gap between research and innovation, that I am eager to pass on to our young scientists. I therefore did not hesitate for a moment when our Dean, Bart Smolders, asked me to lead the center and I am very happy that I took this step.

Sofie Haesaert: I was given a start-up package when I was hired at the TU/e. That was a really nice bonus, since it gave me the opportunity to build my own research line more quickly. This, coupled with the fact that everyone here really embraces interdisciplinary research and has close ties with industry, makes TU/e a great place for a young scientist to build a career.